Sacred Pools

The three sacred crocodile pools of Katchikally in Bakau, Folongko in Kartong and Berending are primarily fertility shrines where, for generations, people have sought help for their problems. Bringing kola nuts as offerings, women come to cure their infertility, men to reverse bad fortune in business, parents to seek protection for their children during the trials of circumcision, wrestlers to achieve victory and more. As Ousman Bojang, the present custodian of Katchikally, squarely put it, “The purpose of the pool is to bring peace to the people”. If the correct procedures are followed it is believed certain that before a year passes the desires of the supplicant will be met.

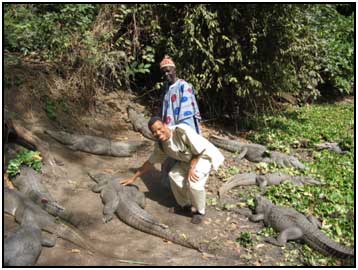

Crocodile Pool at Katchikally

The reptiles in these pools are Nile crocodiles which can grow up to 4.5 metres long and may live for over century. The pools at Bakau and kartong are fed by springs and are covered with a floating plant called water lettuce or ‘pakungo’, while the Berending pool is fed by salt water from nearby streams. A crocodile pool can be visited at the Abuko Nature Reserve though it is not thought to be a sacred place.

Katchikally

According to the legend handed down the Bojang family line, crocodiles were first brought to the pool on the instructions of Katchikally herself, the presiding spirit of the pool. Ousman Bojang, recounting how his family came to be the custodians of Katchikally recalls that his ancestor Ncooping Bojang and his family were the first people to settle in Bakau. One morning whilst sitting in their compound, “Nyamankala”, a woman approached them in great hurry. “Old man”, she said to Ncooping, “my child has fallen into a well, please help me get him out”. Ncooping sent his two sons, Tambaasi and Jaali to help and they took the child out unharmed. It was then that the woman reveaed to them that nothing had actually happened to the child. She had come to find out whether they were troublemakers. But since they demonstrated their kindness by taking the child out of the well, she decided to reveal to them the importance of the place. “God has blessed us with this well you see. He has given it the power to make child-bearing easy.” The two brothers and the woman returned to the compound and told the ageing man all that the woman had said, and why she had chosen them. “God has given this well to me, and I in turn give it to you people”, she explained. The legend has it that Katchikally was the woman’s name and she was a spirit dwelling in the bush who appeared to them in female form. Ousman adds that by saying and doing certain things Katchikally will appear again. His father taught him the means of doing this, but so far he has never tried it because he is too frightened.

The crocodiles at Katchikally live on a diet of frogs found in the vicinity and occasionally bonga fish brought by members of the Bojang family. The two crocodiles originally brought on the instructions of Katchikally have now multiplied to over forty. At the height of the rainy season when the pool is at its fullest young crocodiles are often washed out of the pool.

When a person comes to seek a blessing at the pool, he or she comes with kola nuts which are shared amongst the members of the Bojang Kunda (family), and prayers are said to fulfil his or her wishes. An elder of the family brings water from the pool, the water is blessed, and the person is ritually washed. The ceremony is completed with drumming and dancing. Before leaving, the person is asked to abstain from unbecoming behaviour, for example a woman should abstain from adultery. When the person’s wish is fulfilled, they must come back to make it known.

Kartong Folongko

The custodians of the Folongko pool in Kartong are the Jaiteh family. The presiding spirit of the pool is said to be the daughter of Katchikallly, and so the two pools are closely interconnected.

Berending

The Berending pool serves the same purpose as Katchikally and Folongko though it is fed by salt water and does not have ‘pakungo’ on its surface. It is nevertheless a sacred place.

Sacred Groves, Trees and Stone Altars

Sacred groves, trees and stone altars constitute another category of cultural sites which exist throughout The Gambia. Like other cultural sites they are said to have the potential to ward off evil and bring good to individuals and the community. Various people, particularly the Jola, have sacred groves where they perform religious and other ceremonies such as initiation. Usually a sanctuary for animal and bird life, because of their lush vegetation, such groves are said to be under the charge of or occupied by spirits or divinities. Jola divinities are known to be most effective for disclosing the identities of thieves. Trees usually found in such groves include the baobab and a variety of fruit trees which are often forbidden for eating. It is forbidden to collect firewood from sacred groves.

Mythical’ trees can be found in a number of villages around the country. They are considered sacred by many people who make offerings and sacrifices and say prayers around or under them. They too are associated with God and other spiritual beings. Sometimes they serve as landmarks or mark the graves of legendary people in the society. Stones, hills and caves are also venerated. They too are associated with spirits and divinities and people consult them for their welfare, bringing along offerings of money and food which they deposit in the vicinity.

Sannementereng

The Saano Kunda family of Brufut, are the traditional custodians of Sannementereng. They hold the site in trust for the people of Busumbala who hosted them when they first arrived from Kaabu in the east. The legend has it that one of the elders of Saano kunda was a hunter and in his hunting exploits came across an old man from Busumbala praying in a clearing in the bush that presently constitutes Sannementereng. The old man insisted that he join him in prayers and afterwards revealed that the site is a sacred place and anything prayed for at the spot will be achieved. Hunting was also forbidden within the grounds. When the people of Saano Kunda decided to settle with their host they asked for a piece of land, which they preferred to be near the sea. The host consented to allocate them the area around Sannementereng on condition that they would take care of the place and serve as guides to whoever came for prayers at the site. Proceeds realised from offerings at the site should be shared between Saano Kunda and Busumbala. The ancestor of Saano Kunda agreed to the terms and named their settlement “Tento” (presently Brufut), a Mandinka term for temporary shelter. Soon people started flocking to the site for prayers from all over West Africa because “whatever they pray for, they see” Some come to keep vigil for a week, others for a month. During this time they are provided with food by the Saano Kunda family. In return they pay a fee which also covers the use of the hut that was built for those keeping vigil.

When people come for prayers they report to Saano Kunda from where someone takes them to the site and bathes them in a well at the bottom of the cliff, before they start their prayers. People come to pray for solutions to all sorts of problems, unmarried women to get husbands, barren women to get children, etc. Many return to express their satisfaction and give presents to the custodians.

Saanementereng has been in existence for over 300 years. Its guardian spirit, it is said, is a Muslim and consequently does not do anything bad.

Farankunko

This is a sacred grove located on the outskirts of Dumbutu in the Lower River Region. The land belongs to the Colley Kunda kabilo (family clan) and kafoo (social groups) are found in the area. The grove is used by the whole village to perform special ceremonies usually organised by women. Offerings of kola nut, food, money and clothes are made at the site. The ceremonies are normally accompanied by singing, dancing, cooking and eating. The site is mostly used for praying for rain after long periods of drought.

Santangba

Santangba is the site of a sacred tree located on the outskirts of Brikama, the administrative capital of the Western Coast Region. It is said that when the people of Brikama were leaving Mali it was predicted that there was a special spot where they should settle. They arrived at Kokotali which the king’s marabout identified was the place predicted to them. They cleared the area around a ‘Santango’ tree and settled. From that spot they later moved to Brikama. The site of the tree was therefore regarded as sacred because it was their first settlement. Today, before children are taken for circumcision they must offer prayers at the site. The original tree has now been replaced by a ‘nya yiro’ fruit tree. It is believed that wherever a ‘santango’ tree is found it marks the route taken by their ancestors when they migrated from Mali.

To get there ask for the Chief’s compound in Brikama. From there you can be provided a guide to take you to the site.

Berewuleng

This site is a grove the centrepiece of which is a huge boulder stone. Overlooking the beach at Sanyang village in the Western Division, legend has it that the place was the site of a mosque used by a Muslim jinn who had a long beard and was often seen going to the spot with prayer beads in his hand. Because people believe that the site was his mosque, they go there to say prayer and take along money and food which they place on the boulder. Visitors must however be accompanied by an elder from the village.

To get there ask for the Alkalo’s compound in Sanyang where you can be provided with a guide to take you to the site.

Tombs and Burial Sites

Monuments to the dead constitute another category of Cultural Sites in The Gambia. These usually house the corpses of famous religious leaders, chiefs or soldiers. In most cases the maintenance of such monuments is a family responsibility. Those wishing to visit the sites do not need to consult with the families to do so, unless special prayers are needed. It is not unusual to find devotees of the people buried in such tombs also taking care of the site.

Sait Matty’s Tomb

A rectangular block structure about two metres in height standing in the front garden of the Sun Beach Hotel at Cape Point in Bakau marks the burial site of Sait Matty Ba, a Muslim Fula who led campaigns in the civil war between the Soninkes and Marabouts during the late 1880s. Sait Matty was the son of Maba Diakhou Ba, a devout scholar and jidhadist born of Denianke origins in the Futa Toro. At the height of his jihad Maba moved through the Senegambia displacing the Wollof and Serer populations, ravaging Jola land, destroying the Mandinka kingdoms and posing a threat to French and British interests in the area. Maba was killed 1867 and was succeeded by his brother Momodou Ndare who faced much opposition to his rule. He was challenged by one of his lieutenants, Biran Ceesay, who started another civil war in 1877 in Baddibu and Sine-Saloum which disrupted trade and agriculture on the North Bank. Then in 1884 Sait Matty began fighting Ndare for control of his father’s forces and railed against Biran Ceesay for his inheritance of the rulership of Baddibu. Three years later a peace treaty was negotiated with collaboration of the French and British whereby Sait Matty was to recognise Biran Ceesay’s Lordship over the towns in Sine-Saloum and Niumi and Ceesay was to acknowledge Sait Matty’s over-Lordshhip throughout the entire area.

However, Sait Matty soon invaded Sine-Saloum. The French warned him to withdraw, he refused, and with the co-operation of the king of Sine-Saloum, the French pursued him. Sait Matty fled to The Gambia, took refuge at Albreda, and on 11th May 1887 surrendered to the British.

His defeat plunged Baddibu into a new civil war which threatened to spill over into Sine-Saloum. The French therefore decided to take control of Sait Matty’s towns, disposed of two of Biran Ceesay’s chiefs and authorised local chiefs to collect tributes in Baddibu. Sait Matty then moved to Bakau where he lived quietly until his death in 1897.

Musa Molloh’s Tomb

A Muslim Fula, Musa Molloh Balde was the second ruler of the Empire of Fuladu and son of Alfa Molloh, the founder of the kingdom and a great hunter and king. Fuladu was part of the Fula Confederation that stretched from the Gambia River to the Corubal River in Guinea Bissau and incorporated both British and French territory.

Raiders were annually sent to invade the Upper River Area because the region was under the control of exiled Marabouts who were previously part of the confederation. Shortly after Musa Molloh was born, Alfa Molloh began his uprising (1867-68) against animist Mandinka neighbours who were persecuting the Fula population. Part of his military efforts included establishing Islam wherever he gained control. Alfa Molloh died in 1874 and was succeeded by his brother, Bakary Demba, who was to bequeath the throne to Musa Molloh. Disputes arose over the inheritance but Musa Molloh decided to recognise his uncle as overlord, although for the next decade there were conflicts between the two. Aware of the dangers of civil war, Musa Molloh went south of the Casamance. After Bakary Demba’s death in 1884, Musa Molloh became sole ruler of Fuladu. He became a very useful ally for the British, French and local West African Government in The Gambia as he acted as mediator between these various groups when trying to settle ethnic differences. In 1887 he assisted the French against Momodou Lamin Drammeh, a Soninke marabout who rebelled against foreign domination. In the 1890’s Musa Molloh co-operated with the British in fighting against Foday Kabba, an extremely powerful marabout war leader based in the Kombos who was one of the last opponents of colonial rule. By 1892 Musa Molloh proclaimed himself supreme ruler throughout all of British and French Fuladu. His territory lay on both sides of the arbitrary colonial boundaries, but he lived on the French side. In 1901 he handed over control of British Fuladu to the Government of The Gambia. This transfer made possible the British administration of the protectorate system for all of The Gambia except St. Mary’s Island.

An ordinance of 1902 incorporated Fuladu into the colony which halted the slave trade that Musa Molloh was still engaged in. Two years later, feeling pressured by French colonial interests and being accused by them of tyrannical conduct, Musa Molloh retreated to British territory and settled in Kesser Kunda near Georgetown. Not appreciating his autocratic manner and urged on by the allegations of his enemies, the British exiled Musa Molloh to Sierra Leone in 1919. He was allowed to return to The Gambia in 1923 but without any political power. He died at Kesser Kunda in 1931. His son Cherno Balde was the final ruler of the Empire of Fuladu.

Musa Molloh is renowned as a famous warrior and leader of troops as well as being a skilful diplomat in being able to deal successfully with both the French and British in the midst of Senegambian politics. His tomb was restored in 1971 and was declared a National Monument in 1974. The present structure was built in 1987 in collaboration with the Senegalese Government.

Other Cultural Sites

These include: sacred wells; sites used by renowned personalities for prayers; ant hills; cemeteries; stone circles or isolated stone pillars; caves; mosques; etc. At times associated with special powers, some of them are venerated by individuals and communities and used for prayers and offerings.

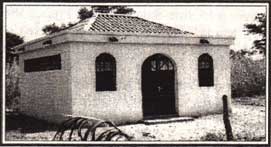

Sand Dune Mosque

Kenye-kenye Jamango is a Mandinka term which literally translates as Sand Dune Mosque. This referred to a makeshift mosque located on the sand dunes overlooking Gunjur beach about 1km from the fishing centre, which is currently under development. The mosque, associated grounds, buildings and rocks are all regarded as sacred because the site provided sojourn for the Kalifat’ul Tijanniyya Sheikh Umar Taal (Leader of the Tijaaniyya Sect in West Africa) during his Islamisation mission in West Africa.

The importance of Sheikh Umar (1793-1864) in the propagation of Islam in the West African sub-region is well documented by his disciples, historians and writers. He is renowned as the man who most significantly earned himself the title Khalifat’ul Tijanniyya through his teachings and holy wars. His pilgrimage to Mecca (1828-1831) and other centres of Islam in the Middle East helped a great deal in accelerating his mission. During his return trip from Mecca he went through Cairo, Bornu, Sokoto, and Madina before reaching Futa Jallon towards the end of 1840. Throughout his journey news of his greatness and erudition preceded him. He was able to eclipse prestigious Marabouts particularly of the Qadiriyya sect which until then was the dominant brotherhood in West Africa.

As one of the notable leaders of the Tijanniyya, with authority from Muhamad Al Ghali, Sheikh Umar took it upon himself to fight ‘paganism’ and challenge the political and social order of the old Muslim theocracies and replace them with a new branch of militant Islam. In 1852 he embarked on a series of military campaigns, imposing his authority from the Senegambia to the Niger. He attracted disciples from all over West Africa including the Aku, or freed slaves of African origin, in Sierra Leone. His Senegambian tour to the north got him into conflict with the Jahanke Marabouts and Qadiriyya sympathisers who did not believe in Jihads as a means of converting people to Islam. He was more successful in the rest of Senegambia where prominent personalities like Alfa Molo and Maba Jahu Bah adopted the Tijanniyya Tarikh in addition to thousands of Mandinka, Wollof, Fula, Soninke and Kasonke disciples who later joined him. Sheikh Umar met up with the French on two occasions, always assuring them of his intention to establish Islam. His vision of establishing a vast Islamic entity posed a threat not only to the established secular order but to the new territorial ambitions of European powers who had started arriving on the Senegambia Coastline.

According to oral sources Sheikh Umar came to The Gambia during the later part of his life when he had adopted peaceful Islamisation as a means of increasing his following. He came to Banjul via Barra in the North Bank Region, and on arrival spent a day under a big fig tree at the Albert Market in Banjul. From there he was taken to Dobson Street by one Ebrima Faye’s wife, whose new-born son he demanded should be named after him. As predicted the boy Sheikh Umar Faye, grew up to be a great scholar, holding positions of trust in both government and the private sector and making valiant contributions during the Second World War. Sheikh Umar Taal also sojourned at Cape Point behind the present site of the Sun Beach Hotel. Here he prayed for peace and protection for the people ad since then the site became sacred and is still visited by people who hold him in high regard. Most importantly, he visited Gunjur, a village on the coast. He found the place serene and suited to holy worship and as a result spent more time at this site than anywhere else in The Gambia. Here, under the shade of trees and huge boulder stones, he prayed at seven spots for God’s guidance and favour. This is how the sacred ground at Gunjur became famous, attracting Islamic scholars and pilgrims from all over West Africa. On his departure the old mosque was built to cater for visitors, some of whom stay several nights in makeshift huts to conduct their vigils.

Touba Kolong

During Maba’s attacks on the Soninke in Sine-Saloum many refugees fled to Niumi particularly around Barra. But due to Amer Faal creating disturbances up-river the British moved about 2000 of the refugees to Bantang Kiling near Albreda and placed them under the leadership of the animist Wollof ruler Masamba Korki.

Masamba Korki and his people suffered periodic harassment from the Muslim Nuiminka, and in 1866 Faal’s followers stole some of their cattle. A Colonel D’Arcy thus organised a punitive expedition of Europeans and Niuminkas to the village of Touba Kolong where Faal had his headquarters. Touba Kolong was protected by a triple log stockade. Led by D’Arcy, 17 volunteers, including 15 men of the Fourth West Indian Regiment, advanced to make a breach in the first stockade. Only two men, Samuel Hodges and Boswell, managed to reach it. Working with axes under heavy gunfire they made a hole in the wall but Boswell was killed in the attempt. D’Arcy was first through the hole followed by Hodges who immediately began to hack through the other two stockades. The rest of the troops entered the village and with the aid of bayonets took control, though the Muslims fought hard and suffered 300 casualties before yielding. Hodges was later awarded a Victoria Cross for his bravery being one of the first Africans to receive this medal of honour from the British.

Oral sources provide a different account of the battle. According to these accounts, beyond the stockades the villagers had dug a well and covered it with leaves and sticks such that when the attackers penetrated the stockade they fell into the well leading to a massive loss of life on the part of the Europeans. To this day Touba Kolong is popular more for this historical ruse than for anything else. The site of the well, which is marked by a huge depression, has been fenced in by the villagers and is now turning into a tourist attraction. Touba Kolong is on the North Bank road leading to Albreda.